No Research, No Results: Why Tactical Discovery Could Be the Most Important Part of Your Digital Innovation Project

Before incurring design costs, you need to know that your idea is desirable for users and commercially viable. Tactical discovery is instrumental to basing your decisions on data, not assumptions, to avoid disastrous consequences downstream.

Most enterprise innovation projects start off on the wrong foot. The focus is wrong, the KPIs are off, or you’re building features for features’ sake with too little emphasis on the nuts-and-bolts of what users need and want—which is why you’re doing the project in the first place.

Before you start developing solutions, it's important to understand the problem. That means doing some focused discovery work to build a clear business case for why we’re solving this particular problem, at this particular time, and in this particular way.

In our last post, we talked about Daito's methodology at the strategy stage of a project—specifically, how current agile approaches are a great way to stack the bricks of a structure but they don’t tell you what shape the structure should take, or what the ideal shape is for the people living in it.

Today, we’re talking about the research phase. This is our structure's foundation. Get it wrong, and you may find that it becomes more cost-effective to knock the structure down and start again, which is a very costly exercise!

Get it right, early

Have you seen the McKinsey stat that 70% of transformation projects fail? Of the many reasons why, a big one is that too many important discoveries are made after a beta is built and deployed to the market. At this point, it costs anywhere between 100 and 10,000 times more to learn the same things that you could have learned with proper research before the design ideation—and certainly before thousands of lines of code are written.

If you had a choice between learning something for $100 or $10,000, which would you choose?

Good design starts in the discovery efforts. Cost of changing requirements increase logarithmically as the product moves towards deployment

In terms of workflow, then, tactical research should sit beneath the vision (strategy division) and above design. The goal is to discover what is possible with the design, what the business goals for the project could and should be, and the requirements that the eventual design will be measured against, while incurring the smallest amount of direct costs. And, more importantly, doing so when the project's committed lifestyle costs are at their smallest.

Just by going ahead through the design process, there’s an exponential increase in your committed costs in getting those requirements right.

Companies that skip the research at the beginning of a project could end up investing 10,000x the amount in fixing things later. That's not our opinion—it's NASA fact.

For research to be reliable, it must be objective

Currently, we live in the golden age of “Design Thinking,” which is the Double Diamond in SAFe. Design Thinking encapsulates something called Design Research, which is a broad term for the art of observing what users say and do, and then using empathy to interpret and act on it. As a qualitative approach, it is more focused on understanding users’ feelings and pain points, rather than measuring interactions, usage and outcomes.

This is positive in many ways. The limitation is bias. The last thing you want when you're gathering information is to enter the field with a biased script that is full of assumptions and might influence what you observe, and what you think you need to observe. This is a recipe for asking the wrong questions and getting the wrong answers.

In our methodology, quantitative data is key. Yes, our researchers will capture and document the emotional experience of users, but it's within the context of their behavior on the ground as they move through their task flows. We focus on the numbers, measuring steps, clicks, movements, time spent on a task, delays, errors, and other empirical evidence to objectively measure human performance.

Getting to that objectivity requires training in the sciences, not design. We've found that practitioners from anthropology, cognitive psychology, behavioral sciences and human factors disciplines are by far the best at scientifically measuring what's going on. Designers are great at empathizing, but they can also fall into design traps and thus create the bias we're trying so hard to eliminate.

In Daito’s methodology, researchers do the research and designers do the design. The best results occur when they collaborate and bring their own speciality to the project.

There are no jokes in nuclear power plants!

Context is everything in digital innovation projects. The research rigor that's required for a cat hotel reservation system is completely different to that of a nuclear sensor alert system. Get the requirements wrong in the first scenario and someone has to make their reservation with a call, not a click. Get them wrong in the second scenario, and the reactor shuts down at the cost of a million dollars a day—or someone dies.

The more complex and dangerous the environment, the more critical it is to measure twice and cut once. While this is as obvious as the nose on your face, few people understand the constraints of performing UX research in extreme environments like an oil rig or power plant. It's like trying to walk into Mordor—even getting on-site is full of challenges and tripwires:

No photos allowed for security reasons (so how do we document things)?

No phones or Bluetooth as they mess with the sensors

40+ hours of training before you're allowed to walk around the plant by yourself to use the bathroom

Radiological training, fire training, hazmat training, psychological profiling, stress training, drug screens, background checks...there are no risk-takers in a power plant, they check!

Need tape to mask off a pipe? You have to measure it and request the exact inches of tape that you need because dropping even the tiniest leftover snippet could cause $25 million worth of damage to a turbine.

Tricky work environment

All of this is standard protocol when visiting a power plant. It explains why your research isn't a “rate your experience” scenario; why we don't—and can't—do the Design Thinking version of discovery, or speak with a couple of users and build a case on empathy alone.

Every discovery project and every site visit should have a bespoke plan, all built around the very specific needs and restrictions of users in these extreme environments.

Context steers the boat!

What’s the output?

A key output of tactical research is goal-oriented task analysis and journey mapping. This is the process of looking at the user's ultimate goal, for example, keeping uptime at 99%, then tracking it back through all the steps and decisions that are needed to accomplish that goal. All those task flow activities we measure? They end up looking something like this:

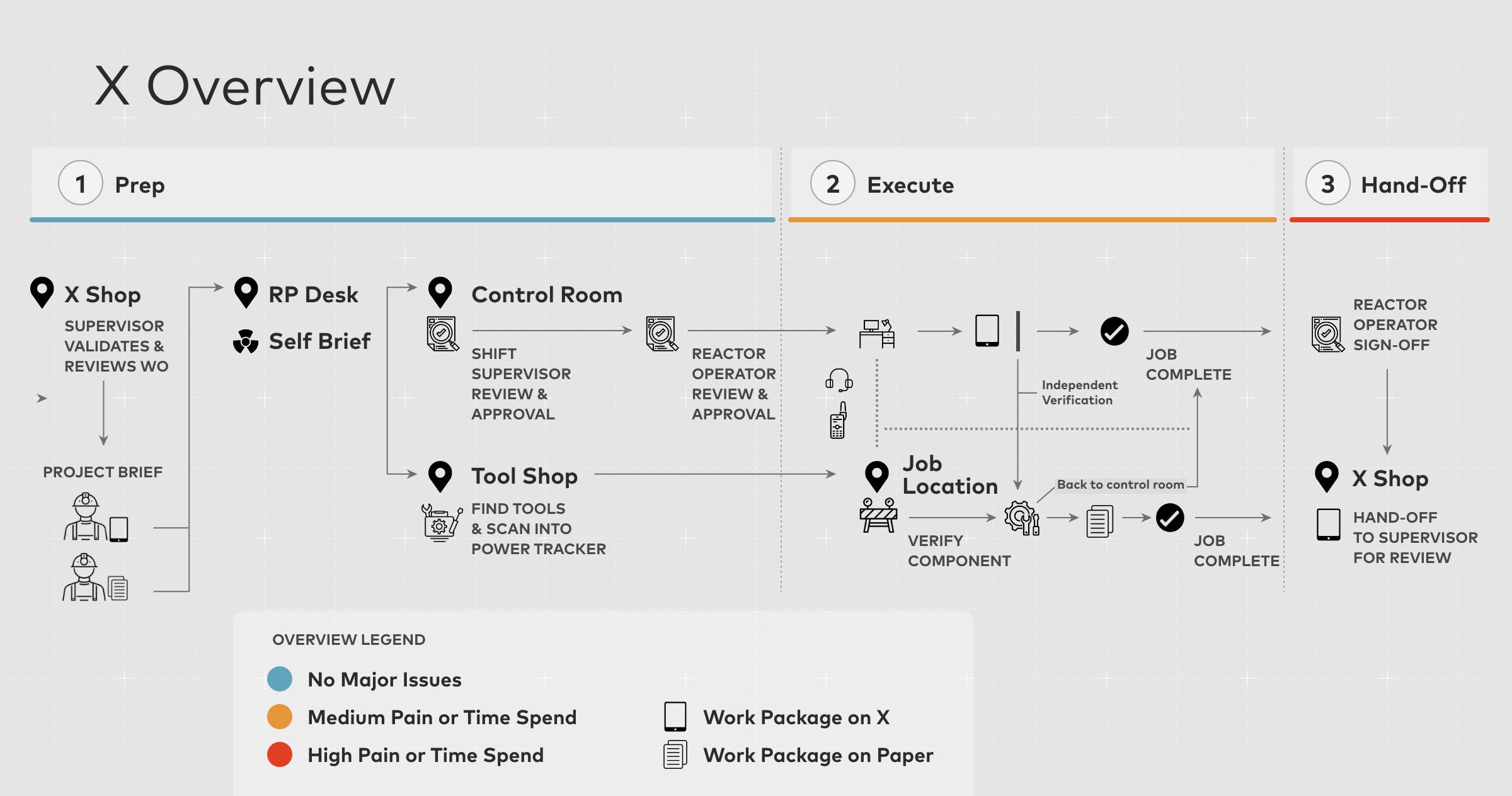

The above diagram shows an overview of the current X technician workflow, including prep work, execution, and hand-off the X.

Then, it's a matter of looking at the cost flow associated with these workflows and identifying areas that can be improved and/or automated. The human-centric goal remains the same, but now we’ve:

Identified ways to shorten the time, increase efficiency, reduce errors etc when delivering that goal

Broken down all of the possible optimizations against their measurable cost potentials and impacts—how many hours can we save in each of these areas? In total?

Calculated a Net Present Value for the project that is grounded in real objective data. And isn’t just guessing.

This is the endpoint of the research phase. Innovation managers now have a set of requirements with hard numbers and ROI-based guardrails to support the design and engineering processes to come.

Tactical research—done early and done right—ensures that transformation projects are more methodological and have a predictable set of outcomes before they are even designed. Anything else is likely to fall victim to what Bent Flyvbjerg calls the Iron Law of Megaprojects—”over time, over budget and under benefit, over and over again.”